Mitigating the Negative Consequences of Living in Civic Deserts – What Digital Media Can (and have yet to) Do

This post is a follow-up to The Conversation piece written by CIRCLE staff, which explored the concept of “civic deserts” and showed that youth who live in civic deserts are less civically engaged and less likely to believe in the power of collective engagement. “Civic deserts,” a new term coined by CIRCLE’s Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg and Felicia Sullivan, refers to a lack of perceived civic opportunities and access to traditional civic institutions.[1]

One key factor that the civic deserts study did not explore was potential interventions and resources that can mitigate the negative effects of living in a civic desert on civic and political participation. Since one-third of all youth, including 60% of young people in rural areas, report living in civic deserts, this elevates the importance of this long-standing question of what role the Internet and social media can play in engaging these young people. As a result, in this brief the following questions are asked to illuminate practices that may help to mitigate the effects of living where traditional civic institutions are not strong or accessible:

- Are civic deserts also places with gaps in internet & mobile access?

- How did youth in civic deserts access information about the 2016 election?

- Is social media serving as an alternative space for civic engagement for youth in civic deserts?

This new analysis of CIRCLE research, based largely on our poll of Millennials conducted in 2016, sheds some light on some of the ways mitigation can occur, where disparities remain, and what mechanisms of online engagement require further study. Findings suggest that online platforms and avenues for civic engagement can narrow the opportunity gap between young people who enjoy access to the physical spaces and resources of traditional civic institutions and youth who live in “civic deserts”—though, notably, it does not eliminate those gaps entirely.[2]

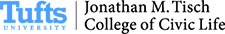

1.Civic Deserts Overlap with Digital Access Gaps, But Not Entirely

Access to digital information and opportunities can be crucial for young people in civic deserts, but often youth must first have the technological infrastructure to get online in the first place. How much is digital access related to perception of being in a civic desert? It turns out that roughly one-third of youth who live in a civic desert do not have access to high-speed internet or reliable cell coverage. By contrast, as seen in the table below, almost all youth who report moderate and high access to traditional civic infrastructure also have access to internet and phone coverage. This means that reliable digital access doesn’t explain everything about whether youth see themselves in a civic desert.

2. Youth in civic deserts didn’t hear as much about the 2016 election, but a great majority saw information on TV

Across all forms of communication, youth in civic deserts were less likely to hear about the 2016 election than youth with more access to civic institutions and resources. While 33% of young people in civic deserts said they heard about the election from friends and family, that number was 48% for youth with moderate access and 62% of youth with high access to civic institutions. The only exception to this dynamic was television news: 73% of youth in civic deserts heard about the election on TV, compared with 75% and 80% for those with moderate and high access, respectively. They were most likely to hear about the election through television news (73%), Facebook (34%), and friends and family (33%).

For some, not hearing about the election may have been a byproduct of the issues with lack of digital access described above, while other youth may have been in environments and cultures where the election was not a frequent topic of conversation even though election-related news was available. Youth in civic deserts read news less often on social media and on news websites. They are also less likely to read about state/national/global events on social media more than one day a week (41% do, compared to 47% among those with moderate access and 52% among those with high access), and they also access online news websites less often than youth with greater access to institutions.

Over half of youth in civic deserts read online news websites more than one day a week (53%), which is less than those who report moderate and high access (60% and 68%, respectively). This may represent differences in internet and mobile reception, or reinforce the lack of civic resources (e.g. a regional news outlet) or civic culture where these young people live.

One response to a perceived lack of access to media is for youth to create their own. In fact, youth in civic deserts were slightly more likely to report posting content they created about politics or social issues. Almost one-quarter of youth in civic deserts (23%) reported doing so in the month before the poll, compared to 16% of youth with moderate access and 12% of youth with high access. Youth in civic deserts without high-speed internet or reliable cell coverage were actually more likely to say that they post content they created at least occasionally. This suggests that in the absence of formalized information, youth in civic deserts are somewhat likely to fill the gap themselves. However, further study is needed to understand the mechanisms and triggers that lead to this creation.

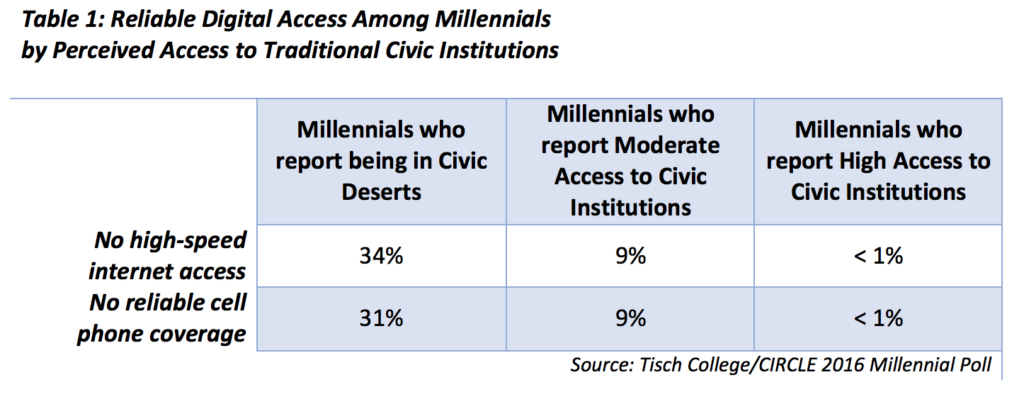

3. Is social media serving as an alternative space for civic engagement for youth in civic deserts?

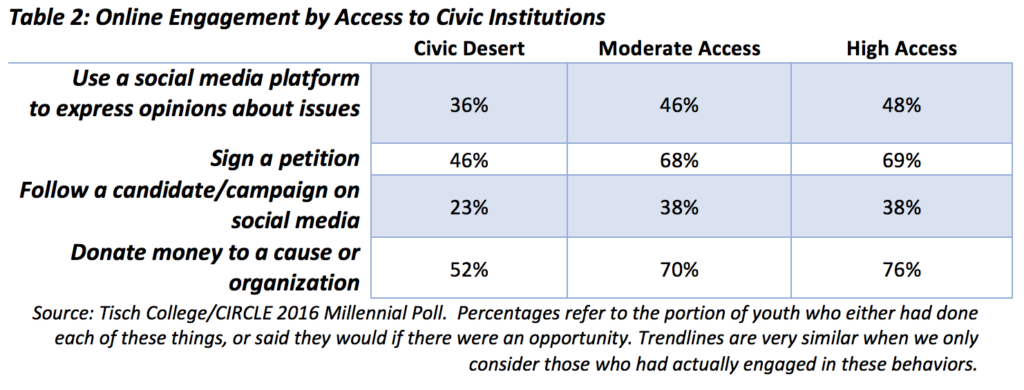

We found that youth in civic deserts, as one might expect, were less engaged in most forms political engagement online (Table 2). That said, there were two exceptions to this trend, where youth in civic deserts were more engaged than others. As shown in Table 3, Millennials in civic deserts were actually more likely to say they were mobilized to action, and that they shared the content on social media.

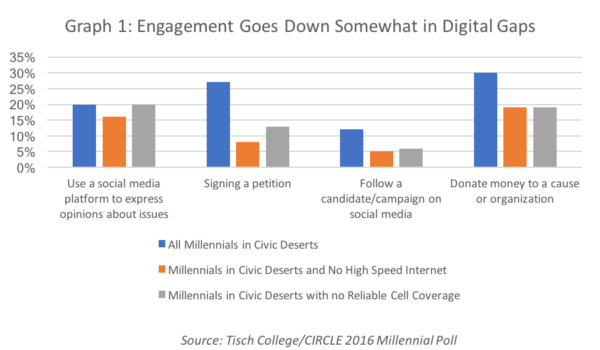

Engagement Even Harder In Digital Gaps

When Millennials lack access to broadband internet or reliable cell phone coverage, in addition to living in civic deserts, they are less engaged, even on digital platforms. One exception is expressing opinions about issues using social media, which did not seem to be markedly affected by additional barriers.

In fact, Millennials in civic deserts without access to high-speed internet or reliable cell coverage may find social media more central to their engagement. These young people without some form of digital access are more likely to say that they decided to take action because of something they read on social media, and to share media related to political and social issues.

There are many possible reasons for these differences, such as access to information or to networks where civic information is shared. Online civic engagement opportunities via social media do appear to be a resource for youth who believe they live in a civic desert, where traditional civic institutions do not seem accessible. Social media is also a way that youth in civic deserts engage by creating media, themselves, to share with others. However, disparities remain, especially on indicators of engagement that might require more connection to a group or campaign. Civic and political organizations would do well to redouble their efforts to engage these youth who may be overlooked and under mobilized despite a genuine eagerness to participate in the life of their communities and democracy.

[1] Our definition of civic deserts centers on the civic alienation that can be felt by youth based on reported perception of the opportunities and resources that they are aware of and that are accessible to them via conventional civic institutions (colleges, nonprofits, community groups, connection to faith-based organizations, arts and cultural activities, etc.) which would provide ready opportunities for in-person engagement in civic and democratic life, as opposed to a measure of the presence of organizations and concrete opportunities. We believe this perception is critical, as youth cannot take advantage of opportunities of which they’re unaware.

[2] Previous work on the topic of civic opportunity and participation gaps has focused on in-school civic education and political participation among youth of color. For examples, see Kahne & Cohen 2013 and Levinson 2012.