On this Page:

Civics is a Crucial Subject | Current Results are Unacceptable |

Some Standard Reform Proposals are Based on Misconceptions | Educating and Engaging Young People Has Positive Long-Term Effects | Effective Practices Develop Civic Skills as well as Knowledge | There are Major Gaps in Exposure to Quality of opportunities | Strengthening civic education requires more support of teachers |

Civic education is a concern for all of us | Resources

Civics is a Crucial Subject

Preparing citizens to be voters, jurors, and members of their communities was the original purpose of public schools. Contrary to popular belief, our survey and federal data indicate that nearly 90% of high school students take at least one civic class, and most states have a requirement. A good civics education also teaches English/Language Arts and skills required for today’s workforce: collaboration, deliberation, public speaking, and more. Dávila and Mora‘s analysis of NELS data shows that youth who have civic learning opportunities are more likely to follow a positive academic trajectory, which can include staying in school and preparing for college.

Current Results are Unacceptable

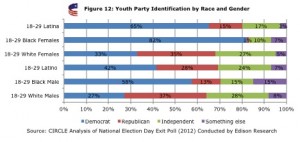

Only a quarter of young people reach “proficient” on the NAEP Civics Assessment, and White, wealthy students are four to six times as likely as Hispanic or Black students from low-income households to exceed that level. Additionally, current policies do not have a significant effect and are not sufficient.

Some Standard Reform Proposals are Based on Misconceptions

For example, we often hear that states should require a civics class. But nearly 90% of high school students already take at least one civic class, usually because of a state requirement. However, in subtler ways, state policies for civics are weak:

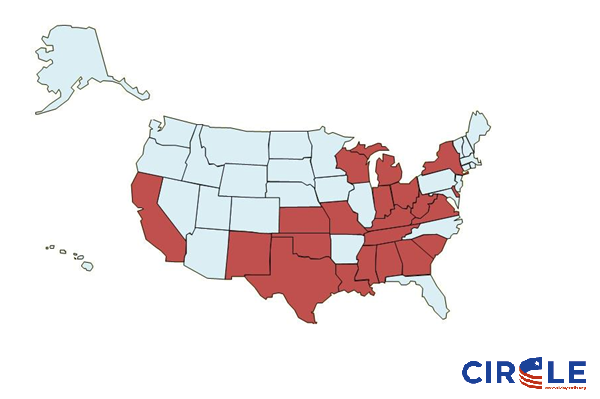

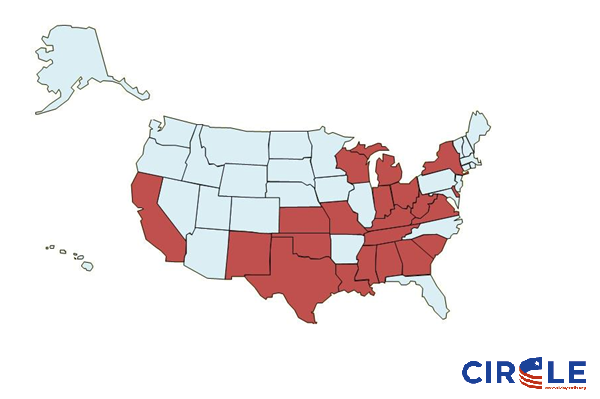

- Eight states (California, Georgia, Kansas, Kentucky, Ohio, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia) include social studies in their assessments of schools’ performance, usually as a very small proportion of schools’ scores.

- Ten states (Arizona, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Massachusetts, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Utah and Wisconsin) require teachers of government or civics to be specifically certified in these disciplines.

- All 50 states and the District of Columbia (D.C.) have a requirement to teach material or offer at least one course in civics and/or government. However, few standards cover skills and dispositions beyond merely factual knowledge.

- 21 states required a state-designed social studies test in the 2012-13 school year.

States that have social studies assessments

Educating and Engaging Young People Has Positive Long-Term Effects

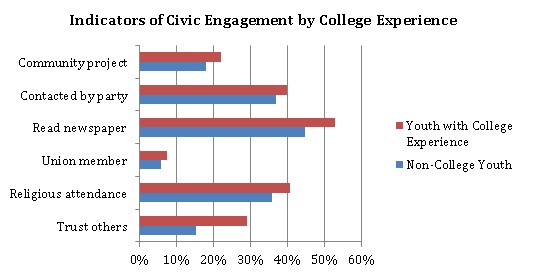

Students who recall having received better civic education are more likely to be engaged. Discussing current controversial issues (one of the six promising practices) seems to boost knowledge and interest. Service-learning is helpful if students feel that they have addressed important social issues (but unhelpful if they do not). Belonging to student groups increases engagement in community life and politics.

The quality of high school civics classes (defined by the number of research-based pedagogical practices that the respondents recalled) marginally predicted young adults’ electoral engagement and their informed voting in 2012.

An evaluation of the Kids Voting USA civics curriculum found that, two years after the program ended, students who participated were still more likely to discuss current issues outside of class and to follow the news than their counterparts who did not participate. (McDevitt and Kiousis 2006)

Effective Practices Develop Civic Skills as well as Knowledge

Good civic education develops skills, such as deliberation, collaboration, and public-speaking. However, achieving those outcomes requires more challenging standards for civics and better integration with other disciplines.

Action Civics is one promising example of methods to increase advanced civic skills such as collaboration and deliberation.

New types of assessments are emerging, like badges, which are portable online certificates that would demonstrate civic skills, knowledge, and actual contributions. They could be awarded by various institutions (e.g. schools and religious congregations) that may share ideas and set standards.

There are Major Gaps in Exposure to Quality of Opportunities

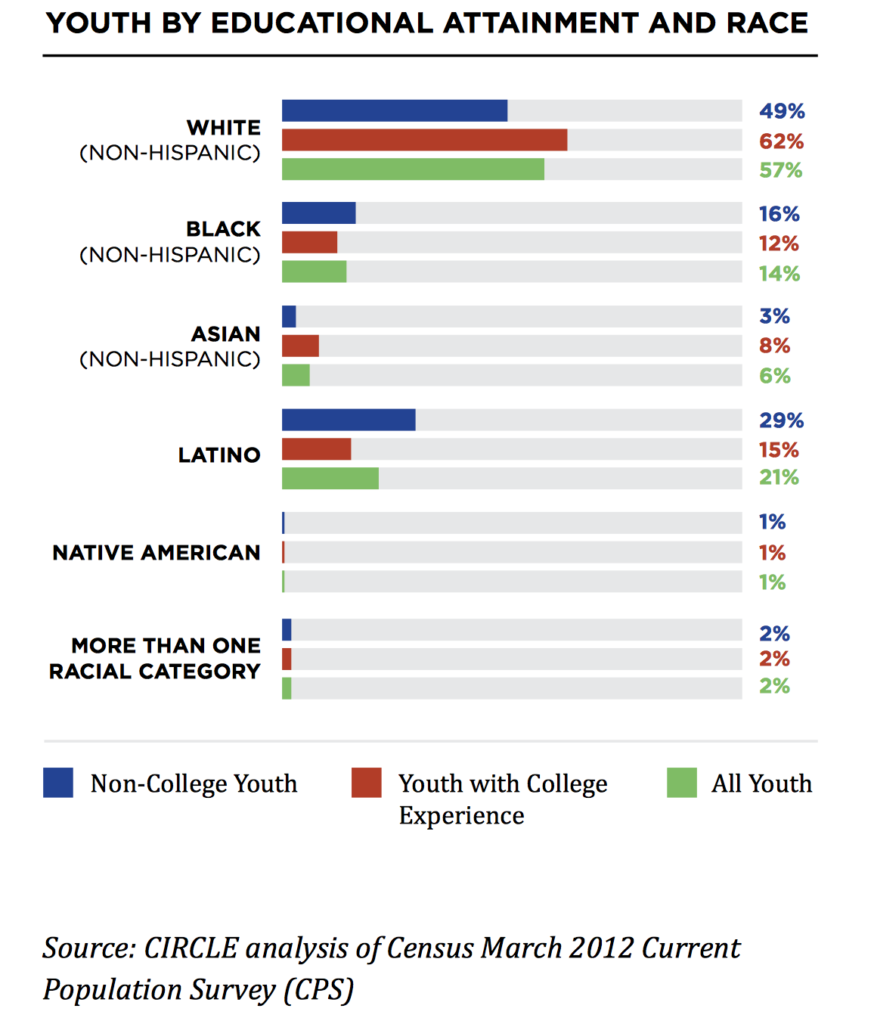

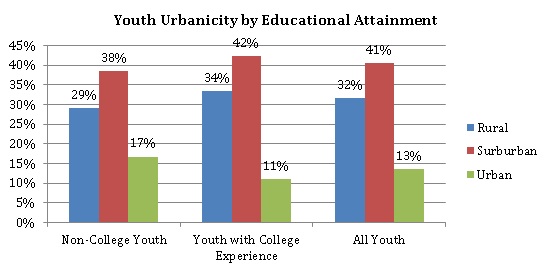

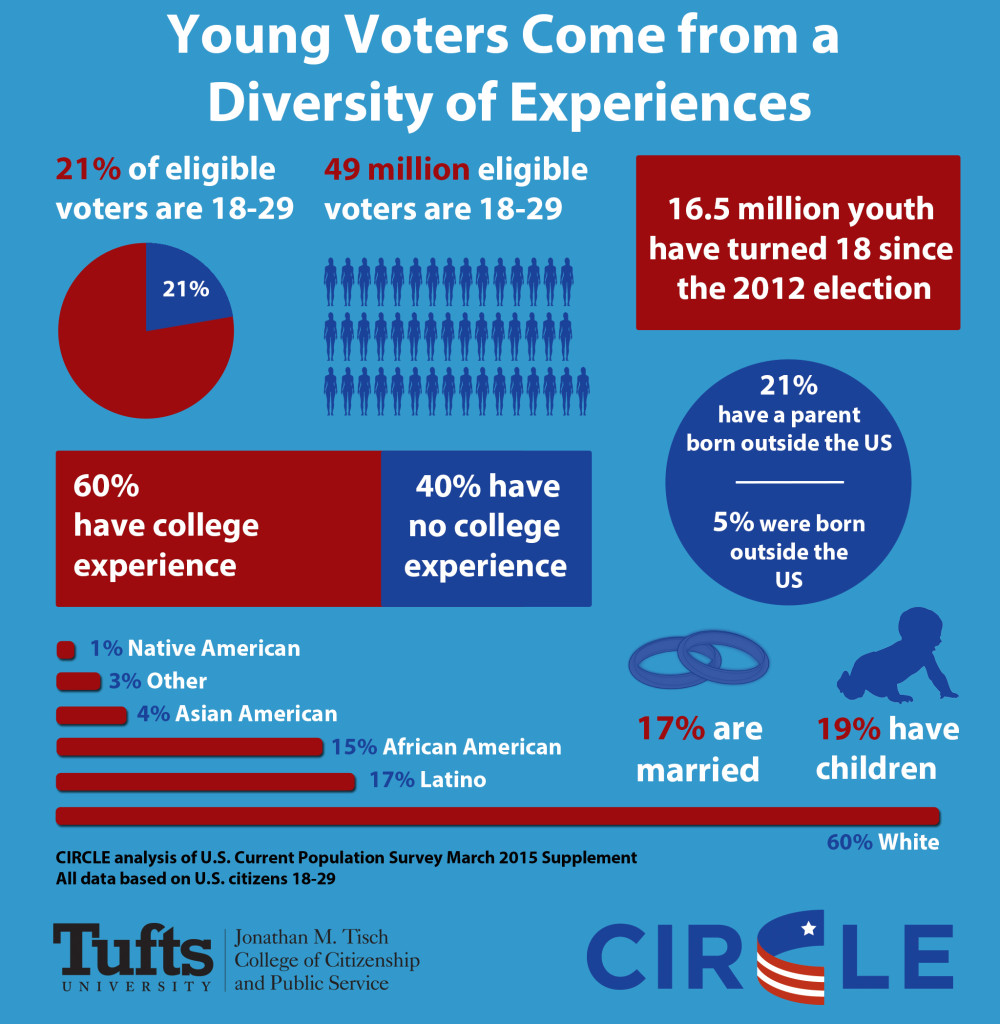

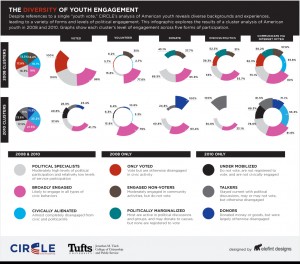

Youth who miss out on civic learning opportunities are more likely to be students of color and low-income young people.

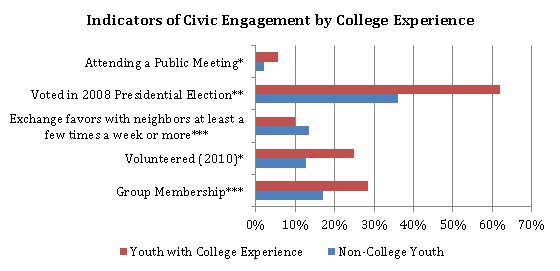

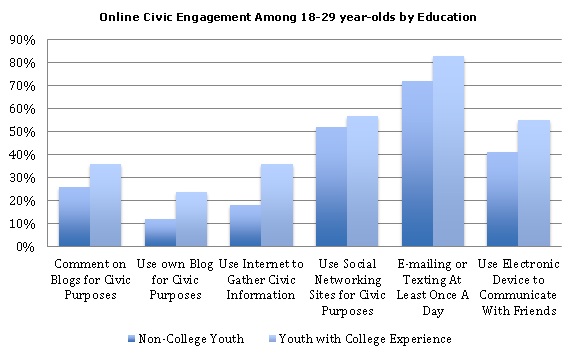

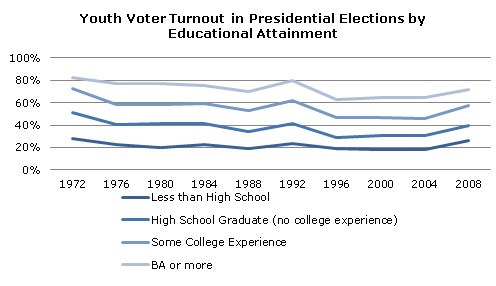

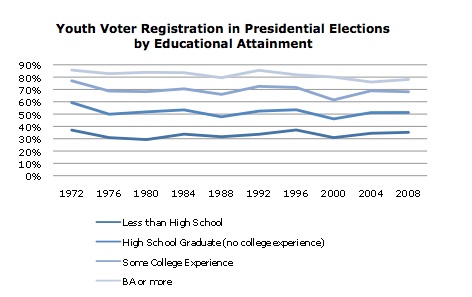

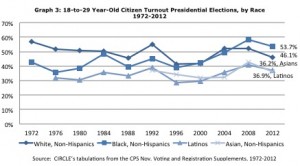

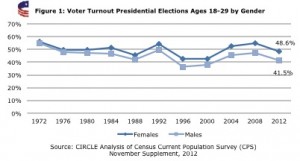

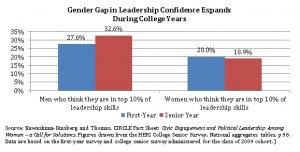

Education, income, ethnicity, and immigration status are all strong predictors of civic participation and civic skill acquisition. Our analysis of various national and federal datasets indicates that this declining national trend in some indicators of civic participation may be due, in part, to declining and unequal opportunities to build civic skills at schools, at home, and in communities and neighborhoods.

Attending racially diverse high schools predicted lower electoral engagement. However, discussion of current controversial issues in school and parental support for controversial discussions diminished the negative relationship between diversity and electoral engagement.

The consequence of unequal civic learning experiences is not only that disadvantaged students lack civic skills, but they also suffer academically.

Strengthening civic education requires more support of teachers

A quarter of teachers we surveyed thought parents would object if they taught about politics in a government or civics class, and only 38% thought their district would give them strong support. Teachers who perceive support are more likely to be using civic education promising practices.

Civic education is a concern for all of us

To have a significant impact on youth civic engagement, we must work together across venues, programs, and sectors, to create a climate in which youth have not just opportunities to learn and participate, but also the skills and efficacy to do so.

Resources

Reports:

Fact Sheets:

Working Papers

Last Updated: 10/8/2013

QUICK FACTS

QUICK FACTS