Political Outreach to Youth Effective in 2018 Midterms, But Many Still Left Out

The 2018 election was the most expensive midterm in modern history, costing $5 billion. While these funds go to many expenses, a significant portion is spent by groups engaging in voter registration, education, and mobilization. The extent to which this voter outreach focuses on youth, many of whom may be newly eligible voters, can tell us a lot about an election. Young voters need to know when and how to register; when, where, and how to vote; and information about the races and candidates. Voter outreach that directly reaches young people and provides this vital information is critical to youth turnout and to expanding the electorate.

Political parties and candidates’ campaigns take on much of this outreach, as they build, manage, and conduct get-out-the-vote operations and other efforts to contact potential supporters. That level of outreach was likely a contributing factor to the substantial increase in youth turnout in 2018.

In this analysis, we explore data from our post-election poll about contact from parties and campaigns to get a clearer sense of what that outreach meant for the 2018 election—and what it means for efforts to engage youth going forward. Among our findings:

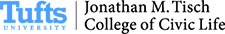

- By Election Day 2018, 52% of young people (ages 18-24) were contacted by a party or campaign, and youth who were contacted before and after the end of September were 33 percentage points more likely to report that they voted.

- 65% of youth who had voted in 2016 were contacted at least once in 2018, compared to 37% of youth who did not vote in 2016.

- Young Democrats were contacted more than young Republicans. In the last six weeks leading up to Election Day, 38% of Democratic youth were contacted and 25% of Republican youth were contacted.

- Young women—especially young women of color—were contacted at higher rates than young men.

Contact Surged and Contact Mattered in 2018

Our pre-election poll revealed that one-third of youth, ages 18-24, were contacted by a political party or campaign before the end of September 2018. According to our post-election poll, more than half of youth (52%) were contacted by Election Day. Just over one-fifth of youth (22%) said they were contacted before October and in the last six weeks before the election.

Contact correlated strongly with higher self-reported turnout. Young people who were contacted either before or after the end of September were 16 percentage points more likely to say they voted last November than those who were not contacted at all. Those who were contacted before October and in the last six weeks of the election were 33 percentage points more likely to vote as those who were not contacted—and about 17 points more likely than those only contacted in either period.

New Voters and 2016 Non-Voters Less Likely to be Contacted

Parties and campaigns tend to reach out to those they believe will support their party or candidates and will actually cast a ballot—especially if they have already done so before. According to our data, past voting and being slightly older were predictive of higher rates of contact. Almost two-thirds (65%) of those who had voted in 2016 were contacted at least once in 2018, among those who hadn’t voted in 2016, just 37% were contacted.

That said, youth aged 18-20, most of whom could not vote in 2016, still reported political outreach from other sources. In our pre-election poll, a substantial number of young people said they were contacted by peers about voting in 2018, indicating that non-candidate/party organizing played a role in mobilizing young people. This may help explain why, in our pre-election poll, despite being less likely to be contacted by political organizations, the percentage of 18 to 20-year-olds who said they intended to vote mirrored that of their slightly older peers.

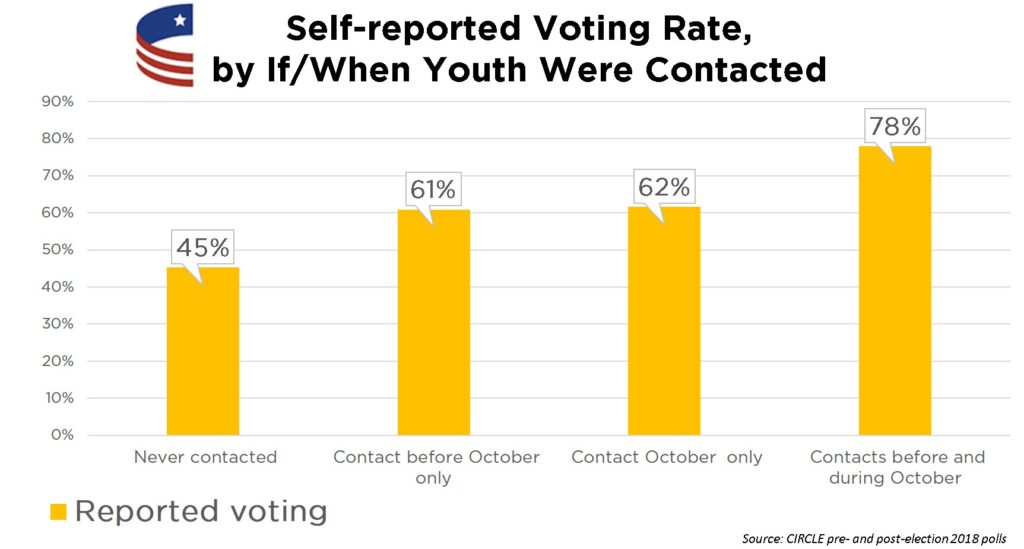

Age was not the only factor that affected contact rates. Even though survey participants under age 21 were generally less likely to be contacted overall, contact rates were also highly affected by current or previous enrollment in college (“college experience” in the graph below). Contact rates varied widely, from just 35% among 18 to 20-year-olds who have never gone to college, to 52% among 18 to 20-year-olds who are currently enrolled in college full-time, and 68% among 21 to 24-year-olds who are currently enrolled in college full-time.

Because, as previously stated, having voted before is also an important factor in whether someone gets contacted, young people with no college experience were far more likely to be contacted if they’d voted in 2016: 33% vs. 58%. That said, their contact rate of 58% still lagged behind their peers who had voted in 2016 and had college experience (68%).

There were also differences by party affiliation. Before the election, we reported that young registered Democrats were more likely than Republican or Independent/Unaffiliated youth to be contacted in 2018. Our post-election poll shows that this trend held through the last six weeks of the election: 38% of Democratic youth were contacted, compared to just 25% of Republican youth. While outreach to Republican youth appeared to increase from its pre-October levels, it’s clear that young Republicans tended to get less frequent and later outreach than Democratic youth. While, as we describe, contact is affected by many factors—especially the competitiveness of electoral races—it is possible that Republican youth are not getting the outreach they should receive from campaigns.

Young Women of Color Contacted at Higher Rates

Based on the available data, there were some differences in contact rates by race and ethnicity. While Black and White you were contacted at least once in 2018 at roughly the same rate (around 55%), with Latino men and women lagged slightly behind (49%).

Gender, however, played a more significant role—in a way that intersects with race and ethnicity. While there was no gender difference in contact rates between White men and women, Black women and Latinas were more likely than their male counterparts to be contacted at least once in 2018, with the largest difference between female (58%) and male (39%) Latinos (see Table). Furthermore, 30% of Latinas say they were contacted both before and after the start of October, while just 8% of Latino men reported being contacted in both time periods. Black women were also 8 percentage points more likely to be contacted than Black men. Our data suggest that difference is due to contact in the final weeks leading up to Election Day, as opposed to earlier in the year.

Although close to half of young White women were contacted (49%), they were the least likely to be contacted when compared to young Black women (60%) and young Latinas (58%). This comparatively higher outreach to young women of color may have been both a reflection and a driver of an election in which a record number of women of color were elected to Congress.

Different Kinds of Outreach, Different Levels of Effectiveness

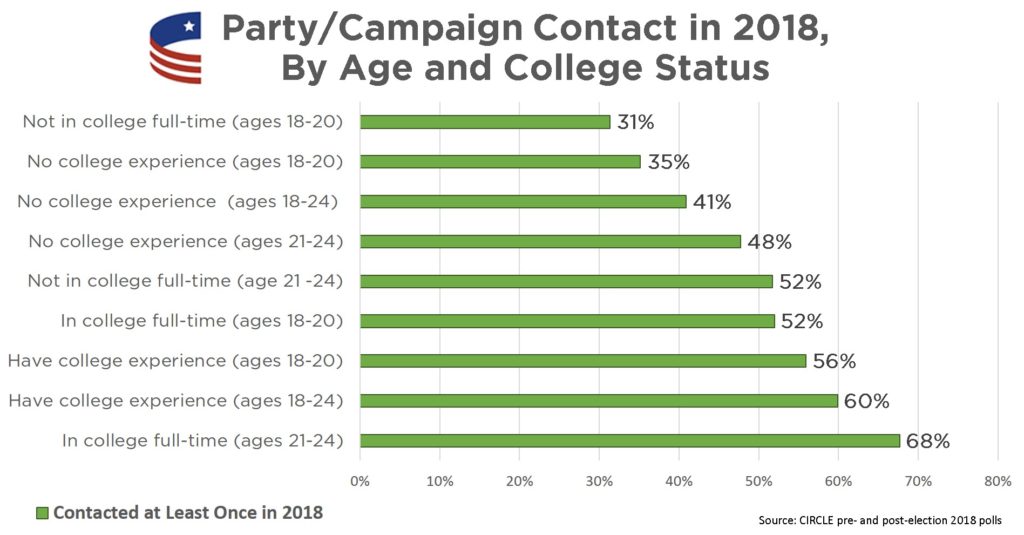

Not all contact and outreach from political campaigns and parties is the same—or is received in the same way by youth. In our poll, we found that outreach via SMS (short messaging services, such as texting) was widespread, especially from Democrats: 37% of youth who said they were contacted by the Democratic Party or Democratic candidates reported being reached via SMS. While there were fewer youth contacted by the Republican Party, Republicans were much more likely than Democrats to reach youth via telephone calls: 42%.

While many people may believe that youth will respond best to technology-based outreach such as SMS, our data add to the growing understanding of the importance of in-person contact. In our survey, the self-reported voting rate was highest among youth who said a party or campaign representative knocked on their door. That said, there may have been other factors driving this correlation; for instance, in-person canvassing may indicate there was an existing relationship conducive to voter engagement.

We also asked what it was like being contacted by a party or campaign. Among youth contacted by Democrats, 33% said that experience was relatively positive, choosing to describe it as “helpful,” “informative,” “interesting,” or “motivating”—compared to 25% of youth contacted by Republicans who described the experience using these positive terms. Broken down by method of contact, youth reached by Democrats were most likely to say door-knocking (45%) and being approached on the street (44%) were relatively positive experiences, while they tended to describe SMS contact and phone calls less favorably.

For young people contacted by Republicans, our data are limited because fewer youth received any contact from the Republican Party or a Republican candidate’s campaign, and even fewer who got a door-knock or on-the-street contact. That said, like youth contacted by Democrats, these young people also found door-knocking to be the most positive experience. Regardless of which political party they were contacted by, the term most frequently used to describe the experience was “annoying.”

Learning Lessons from 2018 to Expand the Electorate

The 2018 midterm election was in many ways an unusual, positive outlier when it came to youth outreach, engagement, and voting. Our data highlight the importance and the effectiveness of actually talking to youth; they also point to some deficiencies in how electoral outreach usually occurs, such as an overreliance on past voting or party registration that inevitably leaves young, new voters behind. To achieve greater scale and equity in youth engagement will require changing or overcoming these and other barriers—some of which we explored in a recent report in conjunction with Opportunity Youth United. Parties and campaigns—as well as election officials, educators, journalists, parents, and peers—all have a role to play in creating more pathways to democratic participation and expanding the youth electorate to more accurately reflect the U.S. population.

—

This is the second in a series of posts about an exclusive new CIRCLE 2018 post-election poll of youth aged 18-24. Read the first post: about the effect of the gun violence prevention movement on 2018 youth political engagement.

The survey was developed by CIRCLE at Tufts University, and the polling firm GfK collected the data from their nationally representative panel of respondents between November 8 and December 7, 2018. The study involved an online surveyed a total of 2,133 self-reported U.S. citizens aged 18 to 24 in the United States, with representative over-samples of Black and Latino youth, and of 18 to 21-year-olds.This survey is a follow-up to CIRCLE’s pre-election survey of 2,087 young people which was fielded in September of 2018. The survey series was designed such that 1,007 of the pre-election survey participants were re-contacted and participated in the post-election survey along with 1,126 new participants who only took the post-election survey. Therefore, this survey allows us to compare the same group of young people before and after the election. The margin of error is +/- 2.1 percentage points, except for the analyses of recontact sample (N = 1,007) which has a margin of error of +/- 3.0%. Unless mentioned otherwise, data below are for all the 18 to 24-year-olds in our sample.